Location & Hours

4008 Red Cedar Dr D-1

Highlands Ranch, CO 80126-8152

| Mon & Fri: | 8 - 4 |

| Tues - Thurs: | 10 - 7 |

Dry eye is a very common problem that affects women more than men and becomes more prevalent as people get older.

Signs and symptoms can range from mild to severe. It can present in many ways, with symptoms that can include a foreign body sensation, burning, stinging, redness, blurred vision, and dryness. Tearing is another symptom and occurs because the eye initially becomes irritated from the lack of moisture and then there is a sudden flood of tears in response to the irritation. Unfortunately, this flood of tears can wash out other important components of the tear film that are necessary for proper eye lubrication.

There are medications that have the potential to worsen the symptoms of dry eye. Here are some of the broad categories and specific medications that have been known to potentially worsen the symptoms:

- Blood Pressure Medications - Beta blockers such as Atenolol (Tenormin), and diuretics such as Hydrochlorothiazide.

- GERD (gastro-esophageal reflux disorder) Medications - There have been reports of an increase in dry eye symptoms by patients on these medications, which include Cimetidine (Tagamet), Rantidine (Zantac), Omerprazole (Prilosec), Lansoprazole (Prevacid), and Esomeprazole (Nexium).

- Antihistamines - More likely to cause dry eye: Diphenhydramine (Benadryl), loratadine (Claritin). Less likely to cause dry eye: Cetirizine (Zyrtec), Desloratadine (Clarinex) and Fexofenadine (Allegra). Many over-the-counter decongestants and cold remedies also contain antihistamines and can cause dry eye.

- Antidepressants - Almost all of the antidepressants, antipsychotic, and anti-anxiety drugs have the propensity to worsen dry eye symptoms.

- Acne medication - Oral Isotretinoin.

- Hormone Replacement Therapy - The estrogen in HRT has been implicated in dry eye.

- Parkinson's Medication - Levodopa/Carbidopa (Synamet), Benztropine (Cogentin), Procyclidine (Kemadrin).

- Eye Drops - In addition to oral medications, many eye drops can actually increase the symptoms of dry eye, especially drops with the preservative BAK.

If you are suffering from dry eye and are using any of the medications above you should discuss this with your eye doctor and medical doctor. Don't stop these medications on your own without consulting your doctors.

Article contributed by Dr. Brian Wnorowski, M.D.

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

In our modern world, people spend hours on end staring at computer screens, smartphones, tablets, e-readers, and books that require their eyes to maintain close focus.

For most people (all except those who are nearsighted and aren’t wearing their glasses), their eyes’ natural focus point is far in the distance. In order to move that focus point from far to near, there is an eye muscle that needs to contract to allow the lens of the eye to change its shape and bring up-close objects into focus. This process is called accommodation.

When we accommodate to view close objects, that eye muscle has to maintain a level of contraction to keep focused on the near object. And that muscle eventually gets tired if we continuously stare at the near object. When it does, it may start to relax a bit and that can cause vision to intermittently blur because the lens shape changes back to its distance focal point and the near object becomes less clear.

Continuing to push the eyes to focus on near objects once the focus starts to blur will began to produce a tired or strained feeling in addition to the blur. This happens very frequently to people who spend long hours reading or looking at their device screens.

An additional problem that occurs when we stare at objects is that our eyes’ natural blink rate declines. The average person blinks about 10 times per minute (it varies significantly by individual) but when we are staring at something our blink rate drops by about 60% (4 times per minute on average). This causes the cornea (the front surface of the eye) to dry out faster. The cornea needs to stay moist in order to see clearly, otherwise little dry spots start appearing in the tear film and the view gets foggy. Think about your view through a dirty car windshield and how much that view improves when you turn the washers on.

So what should you do if your job, hobby, or passion requires you to stare at a close object all day?

Follow the 20-20-20 rule. Every 20 minutes, take 20 seconds and look 20 feet into the distance. This lets the eye muscle relax for 20 seconds, and that is generally enough for it to have enough energy to go back to staring up close for another 20 minutes with much less blurring and fatigue. It also will help if you blink slowly several times while you are doing this to help re-moisten the eye surface.

Don’t feel like you can give up those 20 seconds every 20 minutes? Well if you don’t, there is evidence that your overall productivity will decline as you start suffering from fatigue and blurring. So take the short break and the rest of your day will go much smoother.

Article contributed by Dr. Brian Wnorowski, M.D.

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

If you are seeing the 3 F's, you might have a retinal tear or detachment and you should have an eye exam quickly.

The 3 F's are:

- Flashes - flashing lights.

- Floaters - dozens of dark spots that persist in the center of your vision.

- Field cut – a curtain or shadow that usually starts in peripheral vision that may move to involve the center of vision.

The retina is the nerve tissue that lines the inside back wall of the eye and if there is a break in the retina, fluid can track underneath the retina and separate it from the eye wall. Depending on the location and degree of retinal detachment, there can be very serious vision loss.

If you have a new onset of any of the three symptoms above, you need to get in for an appointment fairly quickly (very quickly if there are two or more symptoms).

If you have just new flashes or new floaters you should be seen in the next few days. If you have both new flashes and new floaters or any field cut, you should be seen in the next 24 hours.

When you go to the office for an exam, your eyes will be dilated. A dilated eye exam is needed to examine the retina and the periphery. This may entail a scleral depression exam where gentle pressure is applied to the outside of the eye to examine the peripheral retina. Some people have a hard time driving after dilation--since the dilating drops may last up to 6 hours, you may want to have someone drive you to and from your appointment.

If the exam shows a retina tear, treatment would be a laser procedure to encircle the tear.

If a retinal tear is not treated in a timely manner, then it will progress into a retinal detachment. There are four treatment options for retinal detachment:

- Laser. A small retinal detachment can be walled off with a barrier laser to prevent further spread of the fluid and the retinal detachment.

- Pneumatic retinopexy. This is an office-based procedure that requires injecting a gas bubble inside the eye. The patient then needs to position his or her head for the gas bubble to reposition the retina back along the inside wall of the eye. A freezing or laser procedure is then performed around the retinal break. This procedure has about 70% to 80% success rate, but not everyone is a good candidate for a pneumatic retinopexy.

- Scleral buckle. This is a surgery that needs to be performed in the operating room. This procedure involves placing a silicone band around the outside of the eye to bring the eye wall closer to the retina. The retinal tear is then treated with a freezing procedure.

- Vitrectomy. In this surgery, the gel - the vitreous inside the eye - is removed and the fluid underneath the retina is drained. The retinal tear is then treated with either a laser or freezing procedure. At the completion of the surgery, a gas bubble fills the eye to hold the retina in place. The gas bubble will slowly dissipate over several weeks. Sometimes a scleral buckle is combined with a vitrectomy surgery.

Prognosis

The final vision after retinal detachment repair is usually dependent on whether the center of the retina - called the macula - is involved. If the macula is detached, then there is usually some decrease in final vision after reattachment. Therefore, a good predictor is initial presenting vision. We recommend that anyone with symptoms of retinal detachments (flashes, floaters, or field cuts) have a dilated eye exam. The sooner the diagnosis is made, the better the treatment outcome.

Article contributed by Dr. Jane Pan

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

When soft contact lenses first came on the scene, the ocular community went wild.

People no longer had to put up with the initial discomfort of hard lenses, and a more frequent replacement schedule surely meant better overall health for the eye, right?

In many cases this was so. The first soft lenses were made of a material called HEMA, a plastic-like polymer that made the lenses very soft and comfortable. The downside to this material was that it didn’t allow very much oxygen to the cornea (significantly less than the hard lenses), which bred a different line of health risks to the eye.

As contact lens companies tried to deal with these new issues, they started to create frequent-replacement lenses made from SiHy, or silicone hydrogel. The oxygen transmission problem was solved, but an interesting new phenomenon occurred.

Because these were supposed to be the “healthiest” lenses ever created, many people started to overwear their lenses, which led to inflamed, red, itchy eyes; corneal ulcers; and hypoxia (lack of oxygen) from sleeping in lenses at night. A new solution was needed.

Thus was born the daily disposable contact lens, which is now the go-to lens recommendation of most eye care practitioners.

Daily disposables (dailies) are for one-time use, and therefore there is negligible risk of overwearing, lack of oxygen, or any other negative effect that extended wear (2-week or monthly) contacts can potentially have. While up-front costs of dailies are higher than their counterparts, there are significant savings in terms of manufacturer rebates. In addition, buying contact lens solution is no longer necessary!

While some patient prescriptions are not available in dailies, the majority are--and these contacts have worked wonders for patients who have failed with other contacts, especially those who have dry eyes.

Ask your eye care professional if dailies might be the right fit for you.

Article contributed by Dr. Jonathan Gerard

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

What do amblyopia, strabismus, and convergence insufficiency all have in common? These are all serious and relatively common eye conditions that children can have.

Did you know that 80% of learning comes through vision? The proverb that states ”A picture is worth a thousand words” is true! If a child has a hard time seeing, it stand to reason that she will have a hard time learning.

Let’s explore amblyopia, or “lazy eye.” It affects 3-5% of the population, enough that the federal government funded children’s yearly eye exams through the Accountable Care Act or ObamaCare health initiative. Amblyopia occurs when the anatomical structure of the eye is normal but the “brain-eye connection” is malfunctioning. In other words, it is like plugging your computer into the outlet but the power cord is faulty.

Amblyopia needs to be caught early in life--in fact if it is not caught and treated early (before age 8) it can lead to permanent vision impairment. Correction with glasses or contacts and patching the good eye are ways it is treated. Most eye doctors agree that the first exam should take place in the first year of life. Early detection is a key.

Strabismus is a condition that causes an eye to turn in (esotropia), out (exotropia), or vertically. It can be treated with glasses or contacts, and surgery, if needed. Vision therapy or strategic eye exercises prescribed by a doctor can also improve this condition.

When we read, our brain tells our eyes to turn in to a comfortable reading posture. In convergence insufficiency, the brain tells the eyes to turn in, but they instead turn out, causing tremendous strain on that child’s eyes while reading. Another tell tale sign of this condition is the inability to cross one's eyes when a target approaches. The practitioner will see instead that one of the eyes kicks out as the near target approaches. This condition can be treated with reading glasses or contacts, and eye exercises that teach the muscles of the eye to align properly during reading. Vision therapy is the treatment of choice for convergence insufficiency.

It is important to understand the pediatric eye and all the treatments that can be implemented to augment the learning process. Preventative care in the form of early eye examinations can mean the difference between learning normally or struggling badly. Remember, a young child can’t tell you if he has a vision impairment. For the success of the child, be proactive by scheduling an early vision exam.

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

Living an overall healthy life is good for your eyes. Healthy vision starts with healthy eating and exercise habits.

There's more to complete eye health than just carrots. Are you eating food that promotes the best vision possible? Learn what foods boost your eye well-being and help protect against diseases. Here are important nutrients to look for when selecting your foods.

- Beta carotene or Vitamin A (helps the retina function smoothly): carrots and apricots

- Vitamin C (reduce risk of macular degeneration and cataracts): citrus and blueberries

- Vitamin E (hinders progression of cataracts and AMD): almonds and sunflower seeds

- Riboflavin (helps your eyes adapt in changes in light): broccoli and bell peppers

- Lutein (antioxidant to maintain health while aging): spinach and avacado

- Zinc (transfers vitamin A to the retina for eye-protective melanin productions and helps with night vision): beans and soy beans

- DHA (helps prevent Dry Eye): Fatty fish like salmon and tuna

Keep in mind, cooked food devalues the precious live enzymes, so some of these foods are best eaten raw.

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

What’s up with people wearing those big sunglasses after cataract surgery?

The main reason is for protection - physical protection to assure nothing hits the eye immediately after surgery, and protection from sunlight and other bright lights.

We want to protect the eye from getting hit physically because there is a small incision in the eyeball through which the surgeon has removed the cataract and inserted a new clear lens. In most modern cataract surgeries that incision is very small - about one-tenth of an inch in most cases. The vast majority of surgeons do not stitch the incision closed at the end of surgery. The incision is made with a bevel or flap so that the internal eye pressure pushes the incision closed.

The incision does have some risk of opening, especially if you were to provide direct pressure on the eyeball. Therefore, immediately after surgery we want you to be careful and make sure that you or any outside force doesn’t put direct pressure on the eye. The sunglasses help make sure that doesn’t happen while you are outside immediately after surgery. It’s the same reason that most surgeons ask you to wear a protective plastic shield over the eye at night while you are sleeping for the first week so that you don’t inadvertently rub the eye or smash it into your pillow.

The other advantage of wearing the sunglasses is to protect your eye from bright light, especially in the first day or two when your pupil may still be fairly dilated from all the dilating drops we used prior to surgery. Even after the dilation wears off, the light still seems much brighter than before your surgery. The cataracts act like internal sunglasses. The lens gets more and more opaque as the cataract worsens and so it lets less and less light into the eye. Your eye gets used to those decreased light levels and when you have cataract surgery the eye instantly goes from having all the lights dimmed by the cataract to 100% of the light getting through the new clear lens implant. That takes some getting used to and the sunglasses help you adapt early on. Think of this as if you were in a dark cave for a long period of time and then were thrust out into the bright sunlight. It would be pretty uncomfortable. The sunglasses help with that adjustment.

So why do people keep wearing those sunglasses long after their surgery? Mostly because some people really like them. They not only provide sun protection straight on, they also give you protection along the top and sides of the frame, reducing the light that can enter around the frame

If you have a spouse who wants to keep wearing those...let’s call them “inexpensive” and “less than fashionable”...sunglasses, but you’d like them to look better, there is a solution. There are sunglasses called Fitovers that go over top of your regular glasses and still provide top and side protection from the sun but look much better than the “free” ones you got for cataract surgery.

Article contributed by Dr. Brian Wnorowski, M.D.

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

Is making an appointment for a comprehensive eye exam for your children on your back-to-school checklist? It needs to be.

No amount of new clothes, backpacks, or supplies will allow your child to reach their potential in school if they have an undetected vision problem.

The difference between eye exams and vision screenings

An annual exam done by an eye doctor is more focused than a visual screening done at school. School screenings are simply "pass-fail tests" that are often limited to measuring a child’s sight clarity and visual acuity up to a distance of 20 feet. But this can provide a false sense of security.

There are important differences between a screening and a comprehensive eye exam.

Where a screening tests only for visual acuity, comprehensive exams will test for acuity, chronic diseases, color vision, and eye tracking. This means a child may pass a vision screening at school because they are able to see the board, but they may not be able to see the words in the textbook in front of them.

Why back-to-school eye exams matter

Did you know that 1 out of 4 children has an undiagnosed vision problem because changes in their eyesight go unrecognized?

Myopia, or nearsightedness, is a common condition in children and often develops around the ages of 6 or 7. And nearsightedness can change very quickly, especially between the ages of 11 and 13, which means that an eye prescription can change rapidly over a short period of time. That’s why annual checkups are important.

Comprehensive eye exams can detect other eye conditions. Some children may have good distance vision but may struggle when reading up close. This is known as hyperopia or farsightedness. Other eye issues such as strabismus (misaligned eyes), astigmatism, or amblyopia (lazy eye) are also detectable.

Kids may not tell you they're having visions issues because they might not even realize it. They may simply think everyone sees the same way they do. Kids often give indirect clues, such as holding books or device screens close to their face, having problems recalling what they've read, or avoiding reading altogether. Other signs could include a short attention span, frequent headaches, seeing double, rubbing their eyes, or tilting their head to the side.

What to expect at your child's eye exam

Before the exam, explain that eye exams aren’t scary, and can be fun. A kid-friendly eye exam is quick for your child. After we test how he or she sees colors and letters using charts with pictures, shapes, and patterns, we will give you our assessment of your child’s eyes.

If your child needs to wear glasses, we can even recommend frames and lenses that would be best for their needs.

Set your child up for success

Staying consistent with eye exams is important because it can help your kids see their best in the classroom and when playing sports. Better vision can also mean better confidence because they are able to see well.

Because learning is so visual, making an eye examination a priority every year is an important investment you can make in your child's education. You should also be aware that your health insurance might cover pediatric eye exams.

Set your child up for success and schedule an exam today!

Have you ever heard of Charles Bonnet? He was a Swiss naturalist, philosopher, and biologist (1720-1793) who first described the hallucinatory experiences of his 89-year-old grandfather, who was nearly blind in both eyes from cataracts. Charles Bonnet Syndrome is now the term used to describe simple or complex hallucinations in people who have impaired vision.

Symptoms

People who experience these hallucinations know they aren't real. These hallucinations are only visual, and they don't involve any other senses. These images can be simple patterns or more complex, like faces or cartoons. They are more common in people who have retinal conditions that impair their vision, like macular degeneration, but they can occur with any condition that damages the visual pathway. The prevalence of Charles Bonnet Syndrome among adults 65 years and older with significant vision loss is reported to be between 10% and 40%. This condition is probably under reported because people may be worried about being labeled as having a psychiatric condition.

Causes

The causes of these hallucinations are controversial, but the most supported theory is deafferentation, which in this case is the loss of signals from the eye to the brain; then, in turn, the visual areas of the brain discharge neural signals to create images to fill the void. This is similar to the phantom limb syndrome, when a person feels pain where a limb was once present. In general, the images that are produced by the brain are usually pleasant and non-threatening.

Treatment and prognosis

If there is a reversible cause of decreased vision, such as significant cataract, then once the decreased vision is treated, the hallucinations should stop.

There is no proven treatment for the hallucinations as a result of permanent vision loss but there are some techniques to manage the condition. Give these a try if you have Charles Bonnet Syndrome.

- Talking about the hallucinations and understanding that it is not due to mental illness can be reassuring.

- Changing the environment or lighting conditions. If you are in a dimly lit area, then switch on the light and vice versa.

- Blinking and moving your eyes to the left and right and looking around without moving your head have been reported as helpful.

- Resting and relaxing. The hallucinations may be worse if you are tired or sick.

- Taking antidepressants and anticonvulsants have been used but have questionable efficacy.

Over time, the hallucinations become more manageable and can decrease or even stop after a couple of years.

If you experience any of these symptoms, please get evaluated by your eye doctor to make sure there is not a treatable eye condition. Don’t be embarrassed or ashamed—your issue is likely caused by a physical disturbance and we are here to help!

Article contributed by Jane Pan

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

Fireworks Eye Injuries Have Skyrocketed in Recent Years

Fireworks sales are exploding across the country through the Fourth of July. As retailers are blazing their promotions, we and the AAO are shining a light on this explosive fact--the number of eye injuries caused by fireworks has rocketed in recent years.

Fireworks injuries cause approximately 15,600 emergency room visits each year, according to data from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. The injuries largely occurred in the weeks before and after the Fourth of July. The CPSC’s fireworks report showed that about 2,340 eye injuries related to fireworks were treated in U.S. emergency rooms in 2020, up from 600 reported in 2011.

To help prevent these injuries, the Academy has addressed four important things about consumer fireworks risks:

- Small doesn’t equal safe. A common culprit of injuries are the fireworks often handed to small children – the classic sparkler. Many people mistakenly believe sparklers are harmless due to their size and the fact they don’t explode. However, they can reach temperatures of up to 2,000 degrees – hot enough to melt certain metals.

- Even though it looks like a dud, it may not act like one. At age 16, Jameson Lamb was hit square in the eye with a Roman candle that he thought had been extinguished. By age 20, Lamb had gone through multiple surgeries, including a corneal transplant and a stem cell transplant to try to restore partial vision to the eye.

- Just because you’re not lighting or throwing it doesn’t mean you’re out of the firing line. An international study of fireworks-related eye injuries showed that half of those hurt were bystanders. The researchers also found that one in six of these injuries caused severe vision loss.

- The Fourth can be complete without using consumer fireworks. The Academy advises that the safest way to view fireworks is to watch a professional show where experts are controlling the displays.

If you experience a fireworks eye injury:

- Seek medical attention immediately.

- Avoid rubbing or rinsing the eyes or applying pressure.

- Do not remove any object from the eye, apply ointments, or take any pain medications before seeking medical help.

Watch the AAO’s animated public service announcement titled “Fireworks: The Blinding Truth.”

Article contributed by Dr. Brian Wnorowski, M.D.

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

Dry Eye Disease affects more than 5 million people in the United States, with 3.3 million being women and most of those being age 50 or over. And as people live longer, dry eye will continue to be a growing problem.

Although treatment options for dry eyes have improved recently, one of the most effective treatments is avoidance of dry eye triggers.

For some that might mean protecting your eyes from environmental triggers. To do that experts recommend using a humidifier in your home, especially if you have forced hot-air heat; wearing sunglasses when outside to help protect your eyes from the sun and wind that may make your tears evaporate faster; or being sure to direct any fans - such as the air vents in your car - from blowing directly on your face. For others, it may mean avoiding medications that can cause dry eyes.

There is one other trigger that may need to be avoided that doesn’t get as much notice: the potentially harmful ingredients in cosmetics.

Cosmetics do not need to prove that they are “safe and effective” like drugs do. The FDA states that cosmetics are supposed to be tested for safety but there is no requirement that companies share their safety data with the FDA. There are also no specific definition requirements for labeling cosmetics as “hypoallergenic,” “dermatologist tested,” “ophthalmologist tested,” “sensitive formula” or the like, making most of those labels more marketing than science.

Things to watch out for in your cosmetics if you have dry eye include:

Preservatives

Preservatives are important to prevent the cosmetics from becoming contaminated but many are known to exacerbate dry eye. Common preservatives in cosmetics that could be adding to your dry eye problems (Periman and O’Dell, Ophthalmology Management August 2016) are: BAK (Benzalkonium chloride); Formaldehyde-donating (yes, Formaldehyde!) preservatives (often listed as DMDM-hydantoin, quaternium-15, imidazolidinyl urea, diazolidinyl urea and 2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol); parabens; and Phenoxyethanol. All of these preservatives in sufficient quantities can cause ocular irritation or inhibit the function of the Meibomian Glands that produce mucous that coats your tear film and keeps it from evaporating too quickly.

Alcohol

Alcohol is used in cosmetics mostly to speed the drying time but the alcohol can also dry the surface of the eye.

Waxes

Waxes can block the opening of the Meibomian Glands along the eyelid margin. If these glands are blocked they will not be able to supply the mucous and lipids necessary to the tear film to prevent it from drying too quickly. If you have trouble with dry eye it would be advisable not to apply eye liner behind the eyelashes along the lid edge where the Meibomian gland openings are.

Anti-aging products

While these may be safe and effective for the skin of the face they should not be used around the eyes. Most of these products contain some form of Retin A. These products have been shown to be toxic to the Meibomian glands and could be contributing to your dry eyes.

These components of cosmetics do not adversely affect everyone. However, if you suffer from dry eye and are not effectively able to keep your eye comfortable and your vision clear, you should investigate your cosmetics as a potential contributor to your problem.

Article contributed by Dr. Brian Wnorowski, M.D.

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

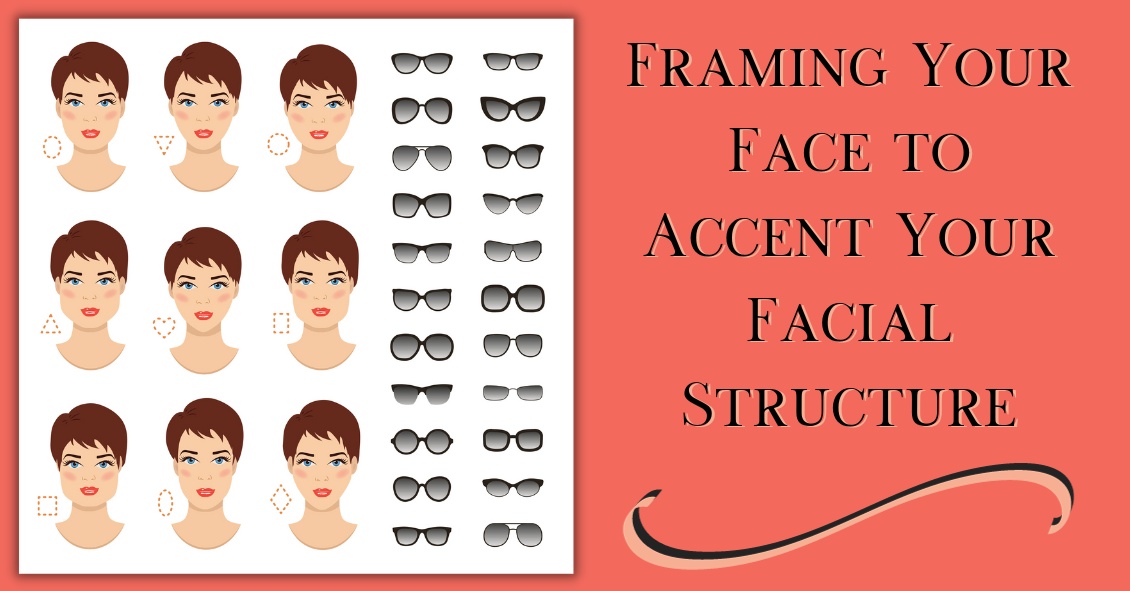

Choosing a new pair of eyeglasses can be a daunting task.

Making a decision on what style glasses you will be wearing for the next year until your vision is checked again can be stressful. This is one of the many reasons opticians are here for you. In many ways, this may be the most important task for the optician, because keeping you happy with the way you look motivates you to wear your glasses daily.

Most people’s reaction is to play it safe with new glasses and stick with something relatively similar to what they are currently wearing.

While not necessarily a bad decision, this isn’t something opticians try to promote. Opticians often spend time meeting with frame representatives and browsing the Internet to keep up with the ever-changing trends in the world of eyeglass frames. And it’s a great feeling to successfully “update” your image with a new set of frames. Many patients are amazed at the difference a well-fit and -styled pair of glasses makes on their overall look.

There are many simple tips and tricks to consider when starting to browse for your next pair of frames.

The goal of this article is to improve your starting point when beginning to choose frames. That way, once the optician gets involved, the process is already well under way. Keep in mind that these are guidelines and “outside the box” thinking can be good as long as it fits within the required parameters of your prescription.

The first step is successfully identifying what face shape category you seem to fit into.

This image shows the most common face-shape categories. The following is a general guideline to help decide which frames will most likely appear to fit the best.

Oval - Oval faces are considered to be the “most versatile” because most frame styles and sizes fit well on this face type. As a general rule, and especially for oval faces, avoid choosing frames that extend past the widest part of your face. Stick with moderate-sized frames.

Upside Down Triangle - To even out the proportions of this face shape, choosing semi-rimless frames is always a positive. Less attention to the bottom half of the frame helps enhance the natural curves of this face shape. Frames that stay wide at the bottom and do not taper inward will also help even out this face.

Oblong - Being longer than it is wide, this face shape enjoys having larger frames on it. A lower bridge will help shorten the nose, and solid dark colors are a positive as well.

Square - A strong jaw line is the focus of this face shape, so to work with that, choosing smaller, narrow frames is a positive. Ovals and rounds work better than squares.

Diamond - Broad cheekbones are the focal point of this face shape. Being quite rare, the best style of frames to put on these faces are in the cat eye family. Following the face’s contours, flare-top frames, semi-rimless frames, and fun colors tend to work well with this shape.

Round - Rectangular frames work best on round faces. Wide bridges help separate the eyes and bring symmetry to the face. Make sure the frames are wider than they are deep.

Triangle - Cat eye frames work exceptionally well with this face shape also. Frames that have a lot of style and accents to the upper part of the frames and temples are a plus as this brings attention to the naturally narrow forehead.

Along with shapes and styles, some believe that certain colors work best with certain faces.

All people are considered to have either cool (blue) or warm (yellow) skin tones. Some people feel customers should stick within their family of coloring. Again this is only a recommendation since you should wear what you like. This is just strictly a guideline for those struggling to choose a frame for themselves. Based on experience, eye color can make a difference as well. People with lighter eyes tend to prefer lighter frame colors, and vice versa for people with darker eyes. Also, hair color can be considered. Patients with lighter or grey hair tend to shy away from darker frames unless looking to make a statement.

At the end of the day you have to choose what is most comfortable for you. Opticians’ suggestions and educated opinions can help steer you in the right direction. There is much to consider, but always keep in mind that comfort and functionality are the priorities.

Some people believe plastic or zyl frames are more comfortable than metal or semi-rimless. Having nose pads, metal frames feel “heavy” to some. Others cannot wear plastic due to oily skin. Plastic frames may slide as the day progresses so metal may be better suited.

Don’t be overwhelmed. Follow some simple guidelines, and remember to enjoy the process. There are infinite styles and options to get you seeing well and looking great. And while you’re considering lenses for your regular lenses, don’t forget to look for sunglasses frames!

Article contributed by Richard Striffolino Jr.

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

What Is Intraoperative Aberrometry?

Yes, that is a mouthful, but the concept isn’t quite as hard as the name.

An Intraoperative Aberrometer is an instrument we can use in the operating room to help us determine the correct power of the implant we put in your eye during cataract surgery.

Cataract surgery is the removal of the cloudy natural lens of your eye and the insertion of a new artificial lens inside your eye called an intraocular lens (IOL).

The cloudy cataract that we are removing has focusing power (think of a lens in a camera) and when that lens is removed, we need to insert an artificial lens in its place to replace that focusing power. The amount of focusing power the new IOL needs has to match the shape and curvature of your eye.

To determine what power of lens we select to put in your eye, we need to measure the shape and curvature of your eye prior to surgery. Once we get those measurements, we can plug those numbers into several different formulas to try and get the most accurate prediction of what power lens you need.

Overall, those measurements and formulas are very good at accurately predicting what power lens you should have. There are, however, several eye types where those measurements and formulas are less accurate at predicting the proper power of the replacement lens.

Long Eyes: People who are very nearsighted usually have eyes that are much longer than average. This adds some difficulty with the accuracy of both the measurements and the formulas. There are special formulas for long eyes but even those are less accurate than formulas for normal length eyes.

Short Eyes: People who are significantly farsighted tend to have shorter-than-normal eyes. Basically, the same issues hold true for them as the ones for longer eyes noted above.

Eyes with previous refractive surgery (LASIK, PRK, RK): These surgeries all change the normal shape of the cornea. This makes the formulas we use on eyes that have had previous surgery not work as well when the normal shape of the cornea has been altered.

This is where intraoperative aberrometry comes in. The machine takes the measurements that we do before surgery and then remeasures the eye while you are on the operating room table after the cataract is removed and before the new implant is placed inside the eye. It then presents the surgeon with the power of the implant that the aberrometer thinks is the correct one. Unfortunately, the power that the aberrometer selects isn’t always exactly right, but with the combination of the pre-surgery measurements and the intra-surgery measurements the overall accuracy is significantly enhanced.

The intraoperative aberrometry is also very helpful in choosing the power of specialty lenses like multi-focal and toric lenses.

We would encourage you to consider adding intraoperative aberrometry to your cataract surgery procedure if you have either a long or short eye (usually manifested as a high prescription in your glasses) or if you have had any previous refractive surgery.

Article contributed by Dr. Brian Wnorowski, M.D.

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

It's pretty common for eye doctors to have older patients come in asking if the white part of their eye, the sclera, has a growth or is turning a gray color.

Usually, the culprit is senile scleral plaque, which is commonly seen in people over the age of 70. It is a benign condition and more commonly seen in women. This condition is symmetrically found on both sides of the eye and is due to age-related degeneration and calcification of the eye muscle insertion into the eye. In one study, the size of the senile scleral plaque increased as the person aged and was not associated with any medical conditions. People are asymptomatic, as the plaques do not affect vision and no treatment is needed.

Another commonly asked question is: Why is the colored part of my eye turning white?

The colored part of the eye is the iris, which is covered by a clear layer called the cornea. It is actually the edge of the cornea that attaches to the white part of the eye that becomes grey or whitish colored.

This condition is called arcus senilis, which is seen in over 60% of people over the age of 60 and approximately 100% over the age of 80. There is no visual impairment and no treatment is needed. Sometimes when this condition is seen in younger patients, it may be related to high cholesterol, so a visit to the primary care doctor may be needed.

These are two very commonly encountered conditions that may cause distress for patients because it seems like their eyes are changing colors.

Thankfully, no treatment is needed for these two conditions, as they do not affect vision. But if you notice that your eyes are changing colors, it is always a good idea to talk with your eye doctor about it!

Article contributed by Dr. Jane Pan

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

After cataract surgery, there are two main issues we try to control: preventing infection and controlling inflammation. Traditionally, we prescribed antibiotic eye drops to prevent infection, as well as steroid eye drops to control post-operative inflammation. But eye drops can be hard for some patients to put into their eyes. Now we have some alternatives to using drops after surgery.

There are some antibiotic solutions we can place inside the eye at the end of the cataract surgery that have been shown in most studies to do as good or better a job preventing infection as using antibiotic eye drops before and after surgery.

The FDA approved steroid delivery methods to reduce post-operative inflammation that have the potential to eliminate post-op steroid eye drops in most (but not all) patients who are undergoing cataract surgery. Two of these products are called Dexycu and Dextenza.

Dexycu is a white bolus of steroid medication that is injected inside the eye after cataract surgery. It will not be visible in most patients because it is injected behind the iris, or the colored part of the eye. It sometimes doesn’t stay behind the iris and you might see a small white dot in the eye initially after surgery. It is a sustained-released medication, which is absorbed over a couple of weeks and replaces the need for post-operative steroid drops.

Dextenza is a white pellet that is inserted into the lower punctum of the lid, which is the small opening for the drainage of tears. This insert is designed to deliver medication for up to 30 days. It is slowly absorbed and doesn't need to be removed. Similarly, it is usually not visible and does not cause any discomfort.

If you have either a Dexycu or Dextenza implant placed and an antibiotic medication is injected inside the eye after surgery, then you may be drop free after surgery. The main difference between the two steroid injections is that Dexycu is injected inside the eye while Dextenza is deposited outside the eye. For each of these newer options there is a chance that in your particular case there may still be too much inflammation and you might need to take eye drops for a while, but the majority of the time you would not need drops.

If you are going to have cataract surgery and would like to be drop free after the procedure, then ask your surgeon if you would be a candidate for a steroid implant.

Article contributed by Dr. Jane Pan.

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

Oftentimes, contact lens wearers will skimp on their lens care because some of the solutions are costly and it seems like a good way to save some hard-earned cash. But this is not a good idea.

Cutting corners can result in infections or irritations, and after one or two copays to your eye doctor's office you probably will have spent more than what you saved in a year by cutting corners--plus you have to deal with your discomfort and inability to wear your contact lenses while you are being treated.

The reasons you clean your contacts is to give increased lens comfort, prolong lens oxygen permeability, and to protect your eyes from infection. The reason you have to disinfect your contact lenses is - as nasty as it may sound - that your eyeball and eyelids are covered in essential bacteria that are kept in check by your body’s immune system. When you remove your contact lens at night it is covered in these essential bacteria. If you don't kill them overnight this will allow the bacteria to grow unchecked and then, instead of inserting a freshly cleaned lens, you are inserting a lens covered in more bacteria than your eye is used to and you end up getting an infection.

Let’s talk about the most widely used type of solution - the multipurpose solution. While this is often the most incorrectly used solution, multipurpose solution is a very safe and effective disinfection method when used properly.

Let’s talk about the most widely used type of solution - the multipurpose solution. While this is often the most incorrectly used solution, multipurpose solution is a very safe and effective disinfection method when used properly.

Many multipurpose solutions advertise themselves as “No Rub.” Just put it in the case and you are done. This is OK to do, but a quick rub with the no-rub solution in the palm of your hand and the opposite hand’s middle or ring finger provide an even better cleaning option. Just the slight roughness of your fingerprint adds a light scrubbing effect that helps improve the removal of surface debris, protein, and mucous better than just letting the lens soak overnight. This rubbing of the lens is especially important for women to remove any cosmetics that are rarely removed by just soaking alone. These few seconds of extra cleaning will make your lenses stay more comfortable longer during their wearing cycle, and help to keep the pores of the lenses open, allowing more oxygen to contact your cornea.

Many name brands and store/warehouse brands of multipurpose solutions exist. All are FDA approved to do the same thing: clean/disinfect/rinse/store your contact lenses. You can't really mess them up unless you try. Remove the lenses, lightly rub them with the multipurpose solution, place your lens into a CLEAN and DRY lens case, and cover the lens with solution to disinfect it. Then let it sit for the number of hours recommended by the manufacturer, generally between 4 to 8 hours, or overnight. Remove the lenses in the morning, rinse with the same multipurpose solution and rinse the lens case out and leave it open to air dry in an area away from your sink and toilet to prevent airborne contaminants from getting into your case as it dries.

The biggest misuse of the multipurpose solution is not changing your case’s solution nightly and just adding more solution to the case each night. We call this “topping off the case.” This is NOT safe because it will lose disinfection power since the old/used solution was busy killing the bacteria and organisms from the night before. Just adding a little fresh solution will eventually allow for the bacteria to take over and you may be adding more bacteria into your eyes than if you never disinfected the lenses to begin with.

Multipurpose solution companies oftentimes will give you a new case when you buy bigger bottles of solution. You should start using the new case with the new bottle of solution. Dont's just stash the case away. There are fungi and other organisms that have been demonstrated to grow from very old lens cases so USE the new case and don't keep it for when you break the old one.

There are many different multipurpose solutions on the market. They aren't cheap and it is tempting to purchase “what is on sale” to save a few dollars. If it does the same thing as the expensive one, then why bother spending the extra? But remember, your contacts are like little sponges that soak up your lens solution. The lens companies don't care if brand A’s solution is compatible with brand B’s or C’s. So over time you can develop a sensitivity to one particular brand of solution, or mixing solutions with the same lens can cause a chemical reaction that occurs because the solutions are not compatible. If you are using the same brand regularly and start having issues your doctor may recommend a solution change to another company that you haven't tried and this may potentially solve your problem. But if you have used several different ones in a few weeks prior to your visit it makes it much harder to determine the cause of your irritation.

The generic/store brands are usually fine products but a grocery store or discount chain doesn’t have a factory that makes their solution for them--they purchase it from a larger supplier. These third-party suppliers can alter their recipe for their multipurpose lens solution and you as the consumer would never know. You could just start finding your contacts are not as comfortable as they used to be and it is actually the unknown generic solution change that is bothering you. Brand name companies like Bausch and Lomb, AMO, and Alcon will rarely make product changes without making consumers aware that they've reformulated the product, so if something changes with the reformulated product you have a better chance of knowing it than with a generic solution manufacturer.

Finally, there is a product called saline solution. Saline is extremely inexpensive, generally half to a third the price of multipurpose solutions. This is a product made by many different companies and was the first lens solution ever used. Saline solution was initially used in a heat disinfection system where the lenses were boiled nightly. The boiling of the lens provided the disinfection, not the saline solution. The solution was to just to prevent the lens from drying out while you cooked it. You should NEVER use saline solution as a replacement for multipurpose solution. Saline solution is NOT a disinfectant for your lenses. It doesn’t contain an agent that will prevent bacteria and organisms from growing in the case overnight. However, it’s totally acceptable if you want to rinse your lenses in the morning with saline prior to inserting them after they were disinfected with your multipurpose solution.

Oftentimes, a practitioner will recommend a certain type of solution to help with things like dryness, environmental allergies, or allergies to specific solutions. I always recommend to check with your practitioner before making any changes to your lens care solution or lens care routine. The best advice for saving money on your preferred solution is buy extra when it is on sale, buy in bulk, and buy what is most comfortable in a multipurpose solution for you. Then stick with it and use it correctly for many years of happy lens wear.

Article contributed by Dr. Jonathan Gerard

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

Sunglasses are more than just a fashion statement - they’re important protection from the hazards of UV light.

If you wear sunglasses mostly for fashion that’s great--just make sure the lenses block UVA and UVB rays.

And if you don’t wear sunglasses, it’s time to start.

Here are your top 6 reasons for wearing sunglasses:

#1--Preventing Skin Cancer

One huge way that sunglasses provide a medical benefit is in the prevention of skin cancer on your eyelids. UV light exposure from the sun is one of the strongest risk factors for the development of skin cancers.

Each year there are more new cases of skin cancer than the combined incidence of cancers of the breast, prostate, lung and colon.

About 90 percent of non-melanoma skin cancers are associated with exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun.

Your eyelids, especially the lower eyelids, are also susceptible to UV light and they do develop skin cancers somewhat frequently.

Many people who now regularly apply sunscreen to help protect them from UV light often don’t get that sunscreen up to the edge of their eyelids because they know the sunscreen is going to make their eyes sting and burn. Unfortunately, that leaves the eyelids unprotected. You can help fix that by wearing sunglasses that block both UVA and UVB rays.

#2--Decreasing Risk For Eye Disease

There is mounting evidence that lifetime exposure to UV light can increase your risk of cataracts and macular degeneration. It also increases your risk of getting growths on the surface of your eye called Pinguecula and Pterygiums. Besides looking unsightly, these growths can interfere with your vision and require surgery to remove them.

#3--Preventing Snow Blindness

Snow reflects UV light and on a sunny day the glare can be intense enough to cause a burn on your cornea--much like what happens when people are exposed to a bright welding arc.

#4--Protection From Wind, Dust, Sand

Many times, when you are spending time outdoors and it is windy, you risk wind-blown particles getting into your eyes. Sunglasses help protect you from that exposure. The wind itself can also make your tears evaporate more quickly, causing the surface of your eye to dry out and become irritated, which in turn causes the eye to tear up again.

#5--Decreasing Headaches

People can get headaches if they are light sensitive and don’t protect their eyes from bright sunlight. You can also bring on a muscle tension headache if you are constantly squinting because the sunlight is too bright.

#6--Clearer Vision When Driving

We have all experienced an episode of driving, coming around a turn, looking directly into the direction of the setting or rising sun, and having difficulty seeing well enough to drive safely. Having sunglasses on whenever you are driving in sunlight helps to prevent those instances. Just a general reduction in the glare and reflections that sunlight causes will make you a better and more comfortable driver.

So it’s time to go out there and find yourself a good pair of sunglasses that you look great in and that protect your health, too.

Your eye-care professional can help recommend sunglasses that are right for your needs.

Article contributed by Dr. Brian Wnorowski, M.D.

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

The eye holds a unique place in medicine. Your eye doctor can see almost every part of your eye from an exterior view. Other than your skin, almost every other part of your body cannot be fully examined without either entering the body (with a scope) or scanning your body with an imaging device (such as a CAT scan, MRI, or ultrasound).

This gives your eye doctor the ability to find many eye problems just by looking in your eye. Even though that makes diagnosing most problems more straightforward than in other medical specialties, there are still many things you can do to get the most out of your eye exams. Here are the top 7 things you can do to get as much as possible out of your exam.

1) Bring your corrective eyewear with you. Have glasses? Bring them. Have separate pairs for distance and reading? Bring them both. Have contacts? Bring them with you and not just the lenses themselves but the lenses prescription, which is on the box they came in. What we most want to know is the brand, the base curve (BC) and the prescription. If you have both contacts and glasses bring BOTH--even if you hate them. Knowing what you like and hate, can help us prescribe something that you will love.

2) Know your family history of eye diseases. There are several eye diseases that run in families. The big ones are glaucoma, macular degeneration, and retinal detachments. If you have a family history of one of these, it may change a doctor’s recommendations for intervention compared to someone without a family history.

3) Know your medical problems. There are several medical problems that correlate with certain diseases of the eye. Diabetes, hypertension, thyroid disease, multiple sclerosis, and autoimmune diseases all correlate with particular eye problems. Knowing your medical history greatly increases the likelihood of more accurately dealing with your eye problem.

4) Know your medications. Several medications are known to produce specific eye problems. Drugs like steroids, Plaquenil, Gleevac, amiodarone, fingolamide, diuretics and Topamax, to name a few, can create problems in your eye. Knowing you are on certain medications may make it much easier for the doctor to arrive at a diagnosis of your eye condition.

5) Be calm and do your best. There are several tests we do that require your participation. The two tests that make people most anxious are the refraction (which determines glasses or contacts prescriptions) and a visual field test (which tests your peripheral vision.) Stay calm and give your best answers. There are no perfect answers. You are not going to get shocked for a wrong answer, so don’t ramp up the anxiety. Just give it your best try.

6) Bring someone with you when possible. There are two reasons for this. One is that it is better to not drive home if you are having your eyes dilated. Many people can do it comfortably, but some can’t. If you are not sure you can drive comfortably with your eyes dilated it is better to have someone with you who can drive home. The second reason is that is always better to have a second pair of ears to hear what the doctor is telling you - especially if the problem is significant. There are many studies that show a person often mishears or misremembers what they have been told, especially if they are anxious. Two pairs of ears are better than one.

7) Write down any questions. It’s very easy to forget to ask something you really wanted to know. You will get your questions answered much better if you have written them down prior to your appointment.

Follow these tips and you will have your best experience possible at your next exam.

Article contributed by Dr. Brian Wnorowski, M.D.

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

At some point, you might be the victim of one of these scenarios: You rub your eye really hard, or you walk into something, or you just wake up with a red, painful, swollen eye. However it happened, your eye is red, you’re possibly in pain, and you’re worried.

What do you do next?

Going to the Emergency Room is probably not your best bet.

Your first reaction should be to go see the eye doctor.

There are many causes for a red eye, especially a non-painful red eye. Most are relatively benign and may resolve on their own, even without treatment.

Case in point: Everyone fears the dreaded “pink eye,” which is really just a colloquial term for conjunctivitis, an inflammation or infection of the clear translucent layer (conjunctiva) overlying the white part (sclera) of our eye. Most cases are viral, which is kind of like having a cold in your eye (and we all know there is no cure for the common cold).

Going to the ER likely means you’re going to be prescribed antibiotic drops, which DO NOT treat viral eye infections. Your eye doctor may be able to differentiate if the conjunctivitis is viral or bacterial and you can be treated accordingly.

Another problem with going to the ER for your eye problem is that some Emergency Rooms are not equipped with the same instruments that your eye doctor’s office has, or the ER docs may not be well versed in utilizing the equipment they do have.

The primary instrument that your eye doctor uses to examine your eye is called a slit lamp and the best way to diagnose your red eye is a thorough examination with a slit lamp.

Some eye conditions that cause red eyes require steroid drops for treatment. NO ONE should be prescribing steroids without looking at the eye under a slit lamp. If given a steroid for certain eye conditions that may cause a red eye (such as a Herpes infection), the problem can be made much worse.

Bottom line: If you have an eye problem, see an eye doctor.

Going to the ER with an eye problem can result in long periods of waiting time. Remember, you are there along with people having heart attacks, strokes, bad motor vehicle accidents and the like-- “my eye is red” is not likely to get high priority.

Whenever you have a sudden problem with your eye your first move should be to pick up the phone and call an eye doctor. Most eye doctor offices have an emergency phone number in case these problems arise, and again, if there is no pain or vision loss associated with the red eye, it is likely not an emergency.

Article contributed by Dr. Jonathan Gerard

This blog provides general information and discussion about eye health and related subjects. The words and other content provided in this blog, and in any linked materials, are not intended and should not be construed as medical advice. If the reader or any other person has a medical concern, he or she should consult with an appropriately licensed physician. The content of this blog cannot be reproduced or duplicated without the express written consent of Eye IQ.

There is an old adage in the eye care industry--Glasses are a necessity, contact lenses are a luxury. Ninety-nine percent of the time this is absolutely true. In the absence of unusual eye disorders or very high prescriptions that don’t allow a person to wear glasses comfortably, contact lenses should only ever be worn if there is a good, sturdy, updated set of prescription glasses available, too. This is due to the fact that there are often emergencies where people cannot wear their contact lenses.

In the 21st century, contact lens technology has gotten to the point where we have drastically cut down on the number of adverse events related to contact lens wear. However, human beings were not meant to wear little pieces of plastic in their eyes. Contact lenses are still considered a foreign body in the eye, and sometimes with foreign bodies, our eyes might feel the need to fight back against the “invader.” As such, issues like red eyes, corneal ulcers, eyelid inflammation, dry eyes, and abnormal blood vessel growth can result from wearing contact lenses.

More often than I would like, I have patients who are longtime contact lens wearers come in, and when I inquire as to the condition of their glasses, they say they don’t own any. My next question is inevitably, “What happens if you get an eye infection and you can’t wear your contacts?” I then see the proverbial light bulb go off in their heads followed by a blank stare. Why? “Because I’ve never had a problem before.” Well, just because you maybe have never been in a car accident before, doesn’t mean you shouldn’t wear your seat belt!

I will therefore repeat the most important takeaway here--Glasses are a necessity, contacts are a luxury. Even if you don’t want to go “all out” and get the most expensive frames or lenses in your glasses, having a reliable pair of glasses is an absolute must for any contact lens wearer.

Article contributed by Dr. Jonathan Gerard